Charles O'Hara on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Charles O'Hara (1740 – 25 February 1802) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer who served in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, and the French Revolutionary War

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

and later served as governor of Gibraltar

The governor of Gibraltar is the representative of the British monarch in the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. The governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government. The role of the governor is to act as the ...

. He served with distinction during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, commanding a brigade of Foot Guards as part of the army of Charles Cornwallis and was wounded during the Battle of Guilford Courthouse

The Battle of Guilford Court House was on March 15, 1781, during the American Revolutionary War, at a site that is now in Greensboro, the seat of Guilford County, North Carolina. A 2,100-man British force under the command of Lieutenant General ...

. He offered the British surrender during the Siege of Yorktown on behalf of his superior Charles Cornwallis and is depicted in the eponymous painting by John Trumbull. During his career O'Hara personally surrendered to both George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

and Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

.

O'Hara's Battery

O'Hara's Battery is an artillery battery in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. It is located at the highest point of the Rock of Gibraltar, near the southern end of the Upper Rock Nature Reserve, in close proximity to Lord Airey's B ...

and O'Hara's Tower in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

were named after him.

Early life

Charles O'Hara was born inLisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, the illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

son of James O'Hara, 2nd Baron Tyrawley and Kilmaine (and eventually promoted Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

in 1763); and his Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

mistress. Charles was sent to Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

. On 23 December 1752, at the age of twelve—a young but not uncommon age for a subaltern of the era—he became a cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a sopr ...

in the 3rd Dragoons

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

. He became a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

in the 2nd Regiment of the Coldstream Guards

The Coldstream Guards is the oldest continuously serving regular regiment in the British Army. As part of the Household Division, one of its principal roles is the protection of the monarchy; due to this, it often participates in state ceremonia ...

on 14 January 1756 shortly before major warfare broke out in Europe.

Seven Years' War

During theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

O'Hara served in Germany as an aide to the Marquess of Granby

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

, the senior officer of the British contingent serving with the Duke of Brunswick

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

's army. In 1762 he served under his father in Portugal in the same campaign with Charles Lee. He also saw service in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Although a disciplinarian

Discipline refers to rule following behavior, to regulate, order, control and authority. It may also refer to punishment. Discipline is used to create habits, routines, and automatic mechanisms such as blind obedience. It may be inflicted on ot ...

, he was extremely popular with the troops under his command.

Senegal

On 25 July 1766, O'Hara was appointed commandant of the Africa Corps inSenegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

, colony which had been captured from France in 1758, with the rank of lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

. This unit was made up of British military prisoners pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

ed in exchange for accepting life service in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. It came at a time when the British government were trying to build up a base in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

. In 1769, he was appointed as a captain in the Coldstream Guards

The Coldstream Guards is the oldest continuously serving regular regiment in the British Army. As part of the Household Division, one of its principal roles is the protection of the monarchy; due to this, it often participates in state ceremonia ...

.

The development of Senegal was a disappointment for the British and O'Hara was uninterested in civil governance. Despite the constitution which had been created offering generous rights to settlers, very few British colonists ever came to West Africa. The territories would ultimately be ceded back to France at the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

in 1783.

American Revolutionary War

In July 1778, Lt. Col. O'Hara arrived in America and immediately commanded forces atSandy Hook, New Jersey

Sandy Hook is a barrier spit in Middletown Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States.

The barrier spit, approximately in length and varying from wide, is located at the north end of the Jersey Shore. It encloses the southern ...

. Lt. Gen. Henry Clinton, commander of the British army in America, gave him that assignment as the French fleet under Admiral d'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, Count of Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the ...

threatened New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

Southern Campaign

In October 1780, O'Hara was promoted tobrigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. In ...

and became commander of Brigade of Guards. He became Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

' second-in-command and good friend. During Cornwallis' pursuit of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependabl ...

to the Dan River

The Dan River flows in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Virginia. It rises in Patrick County, Virginia, and crosses the state border into Stokes County, North Carolina. It then flows into Rockingham County. From there it flows back int ...

, O'Hara distinguished himself at Cowan's Ford, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

on 1 February 1781. He also led the British counterattack at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse

The Battle of Guilford Court House was on March 15, 1781, during the American Revolutionary War, at a site that is now in Greensboro, the seat of Guilford County, North Carolina. A 2,100-man British force under the command of Lieutenant General ...

on 15 March 1781, which led to General Greene withdrawing from the field of battle. He was severely wounded during this battle, but was able to remain with the army as it moved toward Yorktown, Virginia. His nephew, who was a lieutenant of the artillery, was killed during the battle.

Yorktown

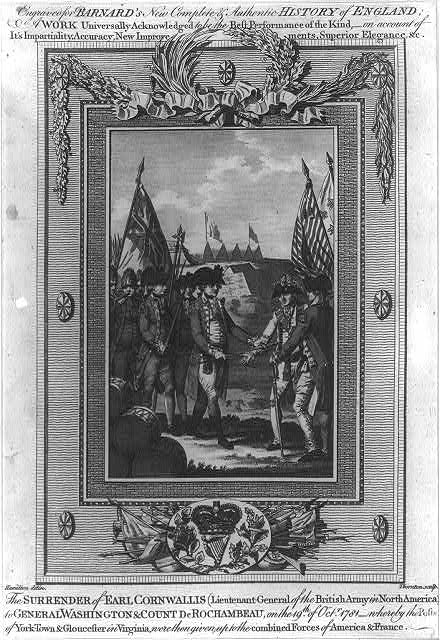

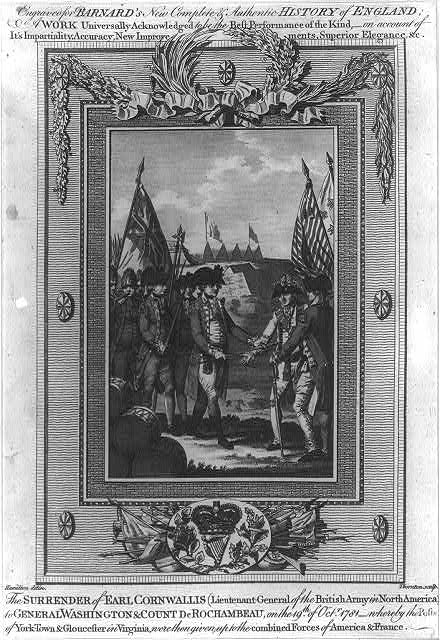

General O'Hara represented the British at the surrender of Yorktown on 19 October 1781, as Cornwallis' adjutant, when the latter pleaded illness. He first attempted to surrender to FrenchComte de Rochambeau

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1 July 1725 – 10 May 1807, was a French nobleman and general whose army played the decisive role in helping the United States defeat the British army at Yorktown in 1781 during the ...

, who declined his sword and deferred to General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

. Washington declined and deferred to Major General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrender ...

, who was serving as Washington's second-in-command and had surrendered to General Clinton at Charleston in May 1780. O'Hara was exchanged on 9 February 1782, and was sent to the Caribbean in command of a detachment of reinforcements. Following the conclusion of the war with the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

he returned to Britain having been promoted to major general.Babits & Howard p.195

The Sword of Surrender

There are various accounts of what became of the surrender sword after the battle: some claim General Washington kept it for a few years and then had it returned to Lord Cornwallis, while some believe the sword remains in America's possession, perhaps in the White House. However, in what is generally regarded as the definitive modern study of the Yorktown campaign, ''The Guns of Independence'' (2005), U.S. National Park Service historian Jerome S. Greene writes simply that O'Hara extended Cornwallis's sword and, "Washington took the sword, symbolically held it a moment, and then returned it to O'Hara." Thus, this most symbolic of war trophies remained with its original owner. The sword was on Antiques Roadshow in 2019, brought there by the wife of his great great great great grandson. It was authenticated and appraised.After the war

In 1784, O'Hara fled from England tothe Continent

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

due to gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three el ...

debts. While in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

he met the writer Mary Berry

Dame Mary Rosa Alleyne Hunnings (; born 24 March 1935), known professionally as Mary Berry, is an English food writer, chef, baker and television presenter. After being encouraged in domestic science classes at school, she studied catering at ...

and began a long relationship with her. After Cornwallis offered him help in paying off his debts, he was able to return to Britain. When Cornwallis was made Governor General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

in 1786 he offered to take O'Hara with him, but he declined.

On 1 April 1791 he transferred from the 22nd Regiment of Foot to be Colonel in Chief of the 74th (Highland) Regiment of Foot.

In 1792, he was appointed lieutenant governor of Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

at the rank of Lt. General.

Toulon

In 1793, he was promoted to lieutenant-general. On 23 November 1793, he was captured at Fort Mulgrove inToulon, France

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is the ...

during operations that gained Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

the attention of his superiors. On the 10th of the same month, Napoleon marched to the siege of Toulon, to retake the hill of Arènes of which Anglo-Neapolitan forces had momentarily taken possession. In this struggle, Napoleon captured the English general O'Hara, who laid down his arms to Napoleon's staff. O'Hara had been leading a bold sortie by the besieged British troops. Napoleon had personally directed the capture operation and accepted O'Hara's formal surrender. O'Hara was treated as an "insurrectionist" and was imprisoned in the Luxembourg Prison and threatened with the guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at th ...

. In the Luxembourg he and his retinue formed a very companionable relationship with a fellow prisoner, the Anglo-American revolutionary, Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

. O'Hara spent two years in prison in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

.

O'Hara thus has the distinction of having been the only person personally taken prisoner by both George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte.

Later years

In August 1795, he was exchanged forComte de Rochambeau

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1 July 1725 – 10 May 1807, was a French nobleman and general whose army played the decisive role in helping the United States defeat the British army at Yorktown in 1781 during the ...

. Later that year he became engaged to Mary Berry, but the engagement was broken when he was named Governor of Gibraltar

The governor of Gibraltar is the representative of the British monarch in the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. The governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government. The role of the governor is to act as the ...

for a second time on 30 December 1795, and she would not leave England. He was promoted to full general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

in 1798. O'Hara is known for the folly that was O'Hara's Tower on Gibraltar and his debates with John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent

Admiral of the Fleet John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent (9 January 1735 – 13 March 1823) was an admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom. Jervis served throughout the latter half of the 18th century and into ...

over the redesign of Gibraltar to serve the needs of the British Fleet. St Vincent, who was admiral in charge of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

, recommended that the Royal Navy Victualling Yard be relocated to the Rosia Bay area, just south of the New Mole. Governor O'Hara did not approve of St Vincent's plan as he proposed to finance it by selling the naval stores at Waterport and Irish Town. However, St Vincent had poor regard for O'Hara, who let the garrison enjoy the ninety pubs on the Rock. It has been proposed that he needed the income to finance his many households and mistresses. St Vincent, however, won with regard to his navy's needs. The poor morale in the garrison led to a plot to let Spain have Gibraltar. O'Hara discovered the plot and 1,000 people were exiled from the Rock.

He died in Gibraltar on 21 February 1802, from complications due to his old wounds and was buried on 25 February.

In popular culture

In theRoland Emmerich

Roland Emmerich (; born 10 November 1955) is a German film director, screenwriter, and producer. He is widely known for his science fiction and disaster films and has been called a "master of disaster" within the industry. His films, most of wh ...

film '' The Patriot'' starring Mel Gibson

Mel Columcille Gerard Gibson (born January 3, 1956) is an American actor, film director, and producer. He is best known for his action hero roles, particularly his breakout role as Max Rockatansky in the first three films of the post-apocaly ...

, Charles O'Hara was played by Peter Woodward

Peter Woodward (born 24 January 1956) is a British actor, stuntman and screenwriter. He is probably best known for his role as Galen in the ''Babylon 5'' spin-offs '' Babylon 5: A Call to Arms'', ''Crusade'' and '' Babylon 5: The Lost Tales''. ...

. His portrayal in the film has been criticised due to the fact the real O'Hara is said to have spoken with a strong Irish accent.

O'Hara was portrayed by Collin Sutton in the television show '' Turn: Washington's Spies''.

John Means portrayed Brigadier General Charles O'Hara in the MGM miniseries ''George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

'' in 1984.

References

Bibliography

* Babits, Lawrence Edward & Howard, Joshua B. ''Long, Obstinate and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse''. University of North Carolina Press, 2009. * Bicheno, Hugh. ''Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolutionary War''. Harper Collins, 2003. * Fredriksen, John C. ''Revolutionary War Almanac''. Infobase Publishing, 2006. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ohara, Charles 1740 births 1802 deaths British Army generals British Army personnel of the American Revolutionary War British Army personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars Cheshire Regiment officers Governors of Gibraltar People educated at Westminster School, London 3rd Dragoon Guards officers 74th Highlanders officers Coldstream Guards officers British people of Portuguese descent Irish colonial officials British Army personnel of the Seven Years' War People from Lisbon